I had promised some recipes in the last blog. But

one good recipe isn't good enough for us. The ingredients each have a story to

tell. The current form can very easily be derived from

socio-political-economical-cultural changes that took place since the whole

thing started. So, it all started in Persia and hence we are going to begin

there.

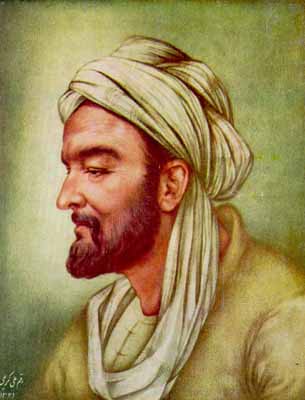

Persia, around tenth century AD, Abu Ali Ibn Sina,

for the first time documented the recipe of Pilaf. Chelow was the

starting point. To make Chelow, the Rice was to be parboiled and drained. The

drained rice was then steamed to get exceptionally fluffy rice with all grains

separated. The Mughal cooks often used to test such rice by dropping a fistful

on ground and checking that no two grains are sticking together. Adding some

spices (and not Ghee, Sugar and Cardamoms) while steaming the rice made it into

Polow. Basmati rice, Sugar, many of the presently prevalent spices were

very expensive in Persia which caused the Polow to taste much like salted,

meaty, colorful rice; color being derived from various flowers and legumes.

While the Polow travelled towards the land of spices and basmati rice, over

Afghanistan, the dry fruits, sugar and spices started becoming more available;

mainly due to newly discovered trading routes and increased trade(and the occasional

invasions).

Arminius Vambery, a Hungarian professor of oriental

languages and a traveller described the Pilaf recipe of the Afghans. A few

spoonfuls of animal fat were melted (the fat of the sheep's tail was preferred)

in a vessel and small pieces of sheep meat are fried and water is added and

boiled till the meat becomes tender. Pepper and thinly sliced carrots are added

to this and is topped with rice. As the rice boils in the water and starts

cooking, some more water is added till it's fully absorbed by the rice. The pot

is then sealed and hot coals are put on top and bottom. The pot is left to

steam for about half an hour. After opening, it is served in such a way that

all layers are separate; carrot and meat on top.

The Afghan recipe although good was too greasy and

insipid to be agreeable to the Indian palate, when it travelled to India. India

was transforming itself to have a religion called Hinduism. The cow had become

sacred and having meat was both expensive and impious. The Mughals also adapted.

Ghee was the substitute used by the Indians for anima fat. Vegetables were the

substitute of meat and good rice was strictly Basmati. And thus the meat

was removed; vegetables were added. Some more aromatic spices and sugar were

added. The Basmati rice was colored with Saffron and turmeric. Animal fat was

replaced by Ghee. The resultant metamorphosed rice is what we love

to call Pulav/Polaoo.

Though I have tracked the journey of Pulav to

India, it also travelled to other parts of the world. The Uzbek Lamb rice, the

Lebanese Rice with lamb shank, and the humble risotto; all were derived from

Pilaf. Pilaf it seems is the great grand parent of all modern recipes that

constitute fluffy separated fragrant rice.

While chatting with a Lebanese Chef, the concepts

of cooking the rice and Pilaf sounded so familiar that I chatted with an Iraqi

and an Indian chef. The exact methods of preparation that they maintain in

their restaurants remain exceptionally the same. Hardly a few percentages of

difference make us all different; it's true for genetics and probably for Pilaf

too.